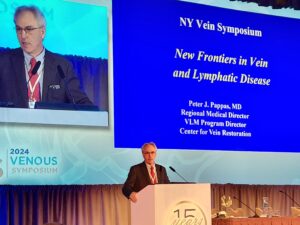

The 2024 Venous Symposium (May 8–11, New York City, USA) was highlighted by keynote speaker Peter Pappas (Chester, USA), regional medical director and program director of the Venous and Lymphatic Medicine Fellowship at the Center for Vein Restoration. Pappas spoke about new frontiers in venous and lymphatic disease management while looking at the past, present, and future of how disruptive technologies have shaped venous treatment.

“It is my hope that in the next 20 to 30 minutes, what I’m about to tell you will inspire a new generation of venous clinicians, researchers, and physicians to do better,” Pappas told the audience.

Pappas began his presentation by speaking about his history as a vascular surgeon. He stated that, when he joined a fellowship at the New Jersey Medical School, he was told “we have this field in venous disease in which there is really not a lot of basic science research. It’s the forgotten stepchild of vascular disease and we really want to elevate the quality of the work that’s being done there.”

“Now, I knew nothing about it. As I read the current literature, I quickly realized my mentors were correct and that this was a career opportunity,” Pappas stated. However, he continued with the fellowship and dedicated his first year to benchwork research and his second year to clinical work.

“I was the first vascular surgeon at that time to get a K08 training grant from the National Institutes of Health,” Pappas continued, “and it opened the door for me for the next 20 years.” Pappas then explained what different grants are currently available, including three types of grants from the American Venous Forum (AVF) for trainees or trained surgeons within the first five years of their careers.

Continuing the discussion on the current state of benchwork research, Pappas referenced a study that was done in a dermatology lab in Europe that was “the last breakthrough in our understanding of the pathophysiology of venous ulceration.

“These investigators determined that macrophages demonstrate different physiologic phenotypes. You have macrophages that regulate tissue destruction (M1 type), and macrophages that regulate tissue repair (M2 type),” Pappas told the audience. “In venous disease, there’s a push towards tissue destruction.”

He explained that iron overload from red blood cell extravasation stimulates macrophages to produce tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha). This cytokine keeps macrophages in the M1 phenotype resulting in ongoing tissue destruction.

Pappas speculated that based on these observations possible future clinical applications could include the utilization of existing TNF-alpha blockers and/or iron chelators to promote wound healing. He added, however, that the current utilization of these drugs have only beed tested in animal models.

Disruptive technologies in venous treatment

“So let’s talk a little bit about disruptive technologies,” Pappas told the audience. “Mark Meissner [University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, USA] and I were talking one day 15 years ago, and he introduced me to the term disruptive technology when discussing the impact the iPhone had on our daily activities.

“I would submit to you that the major disruptive technology in venous disease was the development of the VNUS catheter, which was originally called the Restore catheter. The original intent of this catheter was to restore venous valvular function and not to destroy the vein. After testing the feasibility of restoring valve function, it was discovered that the technique resulted in vein closure and the rise of thermal ablative technologies.

“I remember sitting in the audience in the early nineties when the first clinical data on thermal ablative technologies was presented. I couldn’t believe this actually worked and I was the late adopter too because I wanted to see the data before subjecting patients to this brave new world,” Pappas stated. “As a result, this changed my perspective on the management of venous disease.”

Moving from catheters to stents, Pappas mentioned Raju and Neglen’s groundbreaking paper on the efficacy of Wallstents in patients with venous outflow obstruction. This paper laid the foundation for venous stent outcomes, with Pappas telling the audience that “Raju and Neglen’s results are the gold standard to which all future venous stent trials are measured against.”

Next, Pappas asked: “What are the current needs of patients in the 2020s and going forward? For example, “We haven’t really touched the surface of what we can do” when it comes to compression. When it comes to disruptive technologies and compression, he said that the first use of active sensing technology in a compression device was a major breakthrough. The first device was bulky and cost prohibitive, so it never really saw widespread utilization. Today, there is a new device from Sun Scientific, which I consider breakthrough technology. It’s an all-in-one device that takes the best concepts of what we know about compression.”

The Aero-Wrap compression device allows patients to deliver a specific amount of pressure to their limbs via a handheld pump device. The device also has pneumatic cells that allow it to be converted into a pneumatic pump for lymphedema patients relieving the need to have a compression garment and a separate pneumatic pump.

Another possibility when it comes to future compression devices is the use of sensing technology. Sensing technology will inform physicians of patient compliance, how often they use it, and where the pressure is being applied. Future garments will also provide muscle stimulation through breakthroughs in fiber technology.

Pappas shifted the audience’s attention to thermal technologies.

“As far as I’m concerned, tumescent anesthesia is the biggest problem with thermal technologies,” Pappas said. “This is an engineering problem. I don’t see why we can’t develop a device that can actually penetrate the vein wall and deliver peri-venous tumescent anesthesia.”

Regarding stents, Pappas believes there are still many technological possibilities coming soon. Specifically, he asks whether the industry can develop drug-eluting stents for post-traumatic patients or biodegradable stents for younger patients with non-thrombotic iliac vein lesions (NIVLs).

Future technologies

“What about the future?” Pappas asked near the end of his keynote speech. He believes that, with the advent and continued usage of artificial intelligence (AI), 3D ultrasonography “will be able to give us 3D reconstructions of veins.”

Pappas concluded by look further into the future. “In my lifetime, we will start to see colonization of our solar system. [Research has shown] astronauts returning to earth developed severe lymphedema that took up to six months to resolve. Space travel will require a new generation of doctors trained in Space Medicine,” he said.