Mona Gupta (Chicago, USA) writes about the importance of acknowledging the “complex relationship” between the deep and superficial venous systems.

The complex relationship between the deep and superficial venous systems is an important one to recognize and understand in order to fully treat patients. In the absence of an established treatment algorithm, the clinician must diagnose the coexisting abnormalities and determine which system to treat. Beyond that, the clinician must decide the order in which to treat, and whether both systems actually require treatment to achieve adequate symptom control.

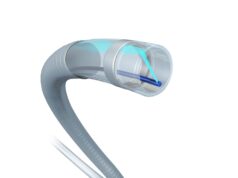

Previously, treatment of chronic venous disease was limited to managing superficial venous reflux caused by incompetent valves. Now, we have a better understanding that the pathophysiology is multifactorial and includes calf muscle pump function, decreased venous compliance, axial deep reflux, and venous outflow obstruction.

Chronic obstruction in the deep venous system commonly results from post-thrombotic inflammation and residual thrombosis or by external compression of the iliac veins.

Multiple studies have proven that treating the outflow obstruction does not worsen the distal reflux.1 Similarly, we have data supporting the treatment of the superficial venous system in the setting of deep reflux and chronic deep vein thrombosis (DVT).2 With this information, we can confidently treat the superficial or the deep or both.

In my clinical setting, that of an outpatient vein clinic specializing in superficial venous reflux, deep venous disease walks in the door daily. Sometimes it is straightforward: the patient with a history of left leg swelling or left leg DVT and absence of superficial venous reflux on standing duplex ultrasound. Or the patient with the recurrent venous leg ulcer (VLU) who has had the superficial system closed.

But most often, it is a more complex diagnosis. The most important risk factors that I have been able to identify in my practice that make me suspect deep venous obstruction are prolonged common femoral vein reflux, out of proportion to the superficial reflux identified; history of DVT and/or inferior vena cava (IVC) filter; recurrent venous ulcer despite adequate treatment of the superficial system and thorough wound care; and recurrent superficial venous disease.

In patients in whom I suspect concomitant deep venous disease, I order a computed tomography (CT) venogram of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate. I then assess the patient’s standing duplex ultrasound and the CT findings, combined with the patient’s symptoms. My general rule is to treat the dominant symptom first.

In patients with edema below the knee or new presentation of a venous ulcer, I am likely to close the superficial system first and monitor the patient’s recovery. In patients with thigh edema, venous claudication, or recurrent/recalcitrant venous ulcers, I am more likely to treat the deep venous system first knowing these patients will likely require a superficial ablation as well.

Suspecting deep venous obstruction in the setting of superficial venous reflux is the first step. The next step is correctly diagnosing the coexisting disease patterns, determining how and when to treat, while prioritizing the patient’s primary symptoms.

References

1. Neglén P, Thrasher TL, Raju S. Venous outflow obstruction: an underestimated contributor to chronic venous disease. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:879–885.

2. Benfor B, Peden EK. A systematic review of management of superficial venous reflux in the setting of deep venous obstruction. Journal of vascular surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders. 2022;10(4):945–954.

Mona Gupta is associate professor of radiology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, USA.

The insights presented on the intricate relationship between the deep and superficial venous systems highlight significant advancements in our understanding and treatment of venous disorders. However, the discussion could be further enriched by incorporating a more detailed analysis of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these conditions. For instance, integrating insights from recent genetic studies or biomarker research could shed light on the predispositions that influence venous pathology and treatment outcomes. Additionally, while the piece aptly discusses clinical practices in diagnosing and treating these complex cases, future discourse could benefit from a comparison of international treatment protocols. This would provide a broader perspective on how different healthcare systems approach similar venous challenges, potentially offering innovative solutions based on cross-cultural practices. Such depth would not only cater to the medical community but also guide policy-making in venous disease management. Thanks.