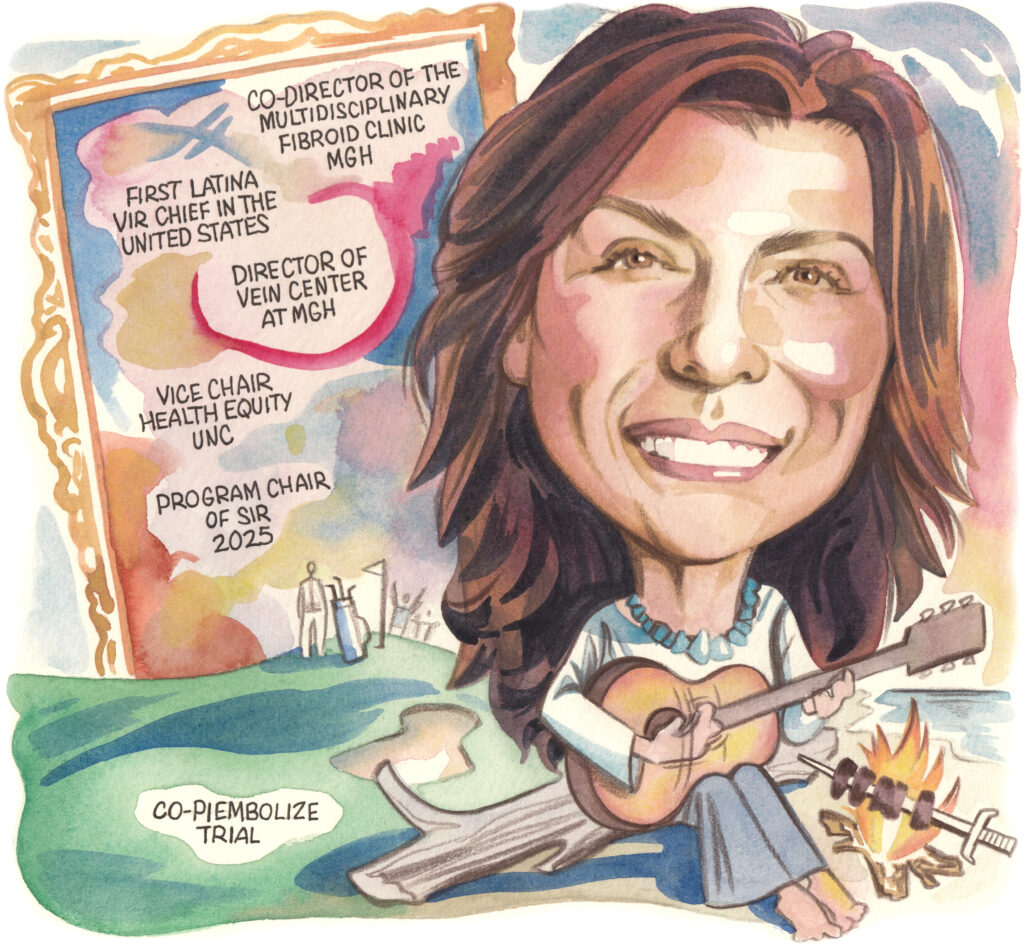

“There are a lot of patients walking out there who are not being treated. So you can only imagine the impact that we can have as specialists to be able to improve those patients’ quality of life,” Gloria Salazar (Chapel Hill, USA) tells Venous News while detailing some of her most memorable patient cases. In this interview, Salazar, the vice chair of health equity & community engagement and associate professor at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Department of Radiology, sat down to discuss her history in medicine, the clinical trials she’s currently working on, and what she would tell prospective medical professionals.

Why did you pursue a career in medicine?

Ever since I was a little girl I wanted to be a doctor—it was between that and being an engineer. When I became a teenager, I had a strong desire to be part of Doctors Without Borders, though that never happened. That desire pushed me to have a career in medicine. I also visited my uncle in the USA when I was a teen. We were at a social event and a doctor friend of my uncle started talking to me about my interest in medicine. He was the first person to tell me that I should consider applying for the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE).

I had early exposure to research when I was in medical school. But, back in Brazil, you have to do a big test and then get accepted into the specialty of your choice. I was really torn because I liked everything—I wanted to do surgery, I wanted to do orthopedics, I wanted to do everything, really. I decided to go for radiology, because radiology encompassed all different specialties.

After I finished my residency in Brazil, I got an opportunity to come to the USA to work as a research fellow at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. I got to work with vascular interventional radiology and fell in love with it. The rest is history.

Who have been your career mentors, and what is the best advice they gave you?

I have been blessed to have several mentors throughout my career, too many to name in this article, but I wanted to specifically mention Salomao Faintuch, Elvira Lang, and Maureen Kohi for giving me the opportunity to make a positive impact in society—for which I will be forever grateful my entire life. Stephan Wicky Van Doyer, Greg Walker, Chris Athanasoulis and Art Waltman for being part of my early career stages that shaped my clinical practice and principles in the moment in my life that I most needed support.

I had amazing mentors in radiology when I was in Brazil including the Department chair, Dr Jacob Szejnfeld. I’m still connected with my mentors, and they have become my friends over the years. I have been very blessed to have so many people helping me in my career, indirectly or directly. Also, I am very thankful for my colleagues—vascular surgeons and interventional cardiologists—who I worked with at Mass General Hospital (MGH; Boston, USA).

Now at UNC, the team that we’ve formed really enhances knowledge, research, and patient care. There are so many people to name. Over the years, I’ve created a good group of connections and people that I can rely on that have helped me and supported me.

What has been the most important development in the venous space over the course of your career?

I think the most important development is that we’re actually paying attention and that there is more awareness of this disease. When I was a fellow we were trained in venous disease, but it was heavily focused on arterial disease. You could rotate into a venous center, but we did not have a robust understanding of the disease process.

Back then we did not have pulmonary embolism (PE) response teams, those came out when I was at MGH in 2012. I think that was a huge development, not only for the treatment of PE, but also for the value of having multidisciplinary teams. I think that’s where we really show how we can make things happen if we work together.

There are other things that have really improved over the last 15 to 20 years. I think we know much more about what we’re doing with our patients and how we do it. I think there is a new understanding that there’s definitely no one-size-fits-all for venous disease in terms of thrombogenic pathways and patient presentation. Really, I think the last 20 years have been fundamental for us to understand where we organize ourselves as specialists.

We also have clinical trials that have started in the venous space that were not even thought of 20 years ago. I think that is the beauty of the evolution and advancement of venous disease. I would say that, in my view, that truly is a testament to collaborative work. There’s no way you can get to this level of advancement without collaboration.

Can you outline some of the trials that you’re currently involved in?

The major trial that I’m currently involved in is the EMBOLIZE trial, of which I’m principal investigator with Dr. Ronald Winokur. A critique of previous publications, and the major critique that leads to the lack of insurance coverage, is that previous studies were unable to select a homogenous patient population. The other critique was, in order for you to really establish that embolization does help reduce chronic pelvic pain in those patients, you need to compare it with an intervention or comparable procedure.

This study was not only to address what has not worked in the past, but also to answer a specific research question, which is whether embolization of gonadals and internal iliac veins do help decrease venous-origin chronic pelvic pain.

With that definition, we also need to exclude patients with other gynecological conditions, because we know chronic pelvic pain is a broad umbrella of different diagnoses. We also devoted a lot of time in our steering committee for the EMBOLIZE trial to develop a protocol that is standardized and is done the same way for everyone.

The patients in our study should not have any obstruction diagnosed by imaging or extra pelvic symptoms, should not have had any surgical interventions in the past, and should not have had any other diagnosis for gynecological causes of chronic pelvic pain.

Our endpoint is visual analog score and differences in the control and in the intervention group. Essentially, patients are going to be randomized to either procedure or venography alone. They’re all going to be blinded as to what intervention they will have.

For the control group, it will be a venography procedure without intervention and without embolization. This is so we can evaluate the placebo effect and also evaluate the differences.

Then we’re going to follow up for the inputs we’re testing for. We’re also looking for quality-of-life questionnaires and specific questions about different symptoms that can overlap with pelvic pain of venous origin. With that, we’re going to follow up with patients both in person and electronically. Then, at six months, we will unblind those patients to what they were treated for and we’ll offer the embolization to the group that was treated with venography alone.

What do you think are some of the major trials that are needed in the venous space?

I think some of the trials that are underway are needed, like the trials that are currently happening in the deep vein thrombosis (DVT) space and the PE space. Now, with the EMBOLIZE trial, I think we still lack understanding on what thrombogenic factors influence outcomes in stenting and in different interventions that we do. But I think this is a more complex question to answer.

I do think we’re going to learn much from the current trials. We also have innovations in valve technology with prosthetic valves being introduced.

I think what is needed is what we’re trying to achieve as a group. When I say as a group, I mean societal groups internationally and nationally, showing how to coordinate those efforts and make sure we are moving this agenda forward in the most efficient manner.

I think this is a great start for future research, protocols that could be developed in the future, and in the venous space. I would say there’s still a lot to be researched, so I don’t think it’s going to get boring on the venous side.

We still have a lot to learn. We’re really just at the tip of the iceberg.

Can you outline one of your most memorable cases?

The most memorable cases are ones where the patient’s life is changed for the better, and I have so many of them, in particular with venous disease. I think that it is very rewarding to see a patient go from no quality of life to being able to spend time with their children and families. I’ve had so many stories of patients that could not go to Disney Land, for example, and they were able to make that trip after we treated them. There are a lot of patients walking out there with diseases and they are not being treated. So, you can only imagine the impact that we can have to be able to improve those patients’ quality of life.

I also do a lot of obstetrics and gynecology (OBGYN) work with high-risk obstetric patients. Every time I see those babies being born and the mom is not bleeding is a memorable moment for me.

What advice would you give someone who is looking to start a career in medicine?

You have to first ask yourself why you want to go into medicine. For me, and for many others that I talk to, it is helping the lives of patients. You can help the lives of patients in different capacities.

If you’re looking for a career in medicine, you need to look inside yourself and see what your core values are. If this career resonates with you, you should learn about it before you go into it. I would strongly recommend you talk to other physicians who are already in the field how happy they feel about it.

It’s hard to talk about this without mentioning the burnout that we’re dealing with—not only in healthcare, but in life in general. So, please, choose a career that makes you happy. I think a career in medicine could be a career with high quality of life, depending on what you do and how you conduct yourself.

You can contribute to the wellbeing of humanity in different capacities, just think about which capacity you want to be in.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I love arts, music, and sports. I’m a big, big fan of soccer. I love going to soccer games and going to concerts and museums. I also love spending time with my friends and family, going to the beach, and playing golf with my son and husband.

A hobby that I have not continued, but did for a long time, is playing the guitar. I love music so much, but it’s been a long time since I’ve done that. Other than that, I just enjoy being in contact with nature.