Johann Chris Ragg speaks to Venous News about the innovations he pioneered and the work that inspired his projects, as well as the challenges and benefits of running a private vascular clinic specialising in endovenous treatments. Ragg recounts his most memorable cases, gives advice to young specialists at the start of their career and discusses what could be the next big thing in venous research and innovation.

Johann Chris Ragg speaks to Venous News about the innovations he pioneered and the work that inspired his projects, as well as the challenges and benefits of running a private vascular clinic specialising in endovenous treatments. Ragg recounts his most memorable cases, gives advice to young specialists at the start of their career and discusses what could be the next big thing in venous research and innovation.

What led you to become a medical doctor, and why did you choose a career in the venous field?

I grew up in a German medical clinic—the building belonged to my grandparents. As a result, all kinds of diseases scared me a lot. During my time as a student, I escaped to solid natural science, in particular physics, but biophysics brought me back to the human body and medicine. I was selected for an interdisciplinary vascular project in Berlin, Germany, responsible for arterial recanalisation lasers.

One morning in 1996 a resident came in and said “do you know some American started to close vessels with lasers?”, before adding, “actually, just veins”. From that very moment, my attention switched from arteries to veins.

What mentors have helped to shape your career, and what lessons have you learned from them?

My first boss at Charité University Clinic Berlin was Professor Giancarlo Biamino, a well-known cardiologist and angiologist. We shared six years in the cath lab and healthcare centre. His dedicated care for patients and his enthusiasm for vascular innovations definitely shaped my career—as well as his habit to skip lunch and see another patient instead.

What have been the biggest developments in the field during your time as a venous specialist?

I jumped on the venous train at a time when endovenous ablation was very exotic, founding my first vascular clinic in the year 2000.

The conversion from vein surgery to endovenous was concluded in our facility until 2005 which was our first year of 100% non-surgical vein repair—in unselected patients of all stages, including recurrences. Meanwhile we did more than 50,000 cases.

Is there a particular study or paper in the last year that you believe had been particularly impactful for your practice?

I am a front-line pioneer linked with and talking to hundreds of authors world-wide via our website, venartis.org. Some papers are entertaining, some studies are scientifically brilliant, but the impact on daily practice is low, compared to our own discoveries. Our structures allow me to practice ultrasound for four to six hours a day while treating or checking patients and training assistants, and every new machine shows more real-time details of valve behaviour. That is inspiring!

I feel sorry for all those who do not have the pleasure to du ultrasound of vein valves themselves. The best source of input were those precious moments of intimate knowledge exchange with friends while enjoying a glass of wine, in a conference night or during a private visit, or best of all: while treating patients together. To give some examples of what and who has inspired my projects, these include: effects of blood proteins on sclerosants (Parsi/Connor, for novel foam), water compression (Gianesini, Obermeyer, for the film bandage), insights in haemodynamics (Lurie, Lattimer), valve anatomy (van Rij, Maleti) aesthetics (Miyake), and many others.

You set out early as an independent founder of a private interventional vein clinic. What did this experience teach you?

At the start of my career, I was a trained university researcher in the arterial field for six years. When I changed my focus to veins, I started fresh and kind of refined, with a clear analysis and strategy. This was based on several important questions, including: Which is the most frequent venous disease? Which are the most frequent practical problems at present? Which is the fastest way to improve patients’ fates? Which is the fastest way to obtain reliable and essential study results?

My private facilities, which incorporate clinic, outpatient services, research and training activities, offer the advantage of simple structures, fast decisions and fast corrections—thus creating shorter learning curves. Another plus is the ability to have a very close relationship with the patients, with unfiltered communication of their satisfaction. As for any disadvantage and potential limitations of running an independent private clinic, there is the economic aspect. To stay independent by our standards, we never accepted money from any company for product studies. However, limited finances mean limited scientific outcome. We could have done much better and produced more work with more staff.

In the last decade, you have pioneered treatments such as percutaneous valvuloplasty and invented the transparent film bandage. How were your innovations conceived, and what impact have they had on practice?

It is the compression film bandage which makes foam sclerotherapy of varices become a true alternative to phlebectomy—but faster, less invasive and painless. Seventy per cent of our patients receive it. Unfortunately, the manufacturer would like to have a single worldwide product, including countries with warm and humid climates. More studies have to be done, wasting time to general marketing. Hyaluronan valvuloplasty is still experimental although we use it every day, searching for optimal products, tools and procedures. For example, monophasic gels of lower viscosity allow precise small-lumen injection and easy spatial distribution, but biphasic gels with larger particles provide better long-term residence. One option is amazing: multifocal vein lumen reduction to normalise a vein’s volume load. It is much more specific than a compression stocking. To clarify haemodynamic relations, you use a fast-resorbable but solid hyaluronan. If successful, you replace it with long-term products. Some cases seem to heal in spite of hyaluronan degradation. It is a new world.

What are your current research or innovation interests?

As vein killing is still daily business, we work on improvements of vein gluing (ScleroGlue project) and a novel viscous sclerofoam, using an approved chemistry (Biomatrix sclerofoam) for one-step treatment of extended tortuous targets and malformations. However, we consider endoluminal treatment as a transitional phase of one, two or three decades to be replaced by specific prevention or minimal early stage repair.

My current number one focus is on congenital vein valve lesions. In an ongoing study, we found 55.6% of children and adolescents with at least one malformed leg vein cusp. About 85% of these lesions cannot be detected except when using high resolution ultrasound (16–32MHz). Secondary focus for me is the detection of motion-resistant aggregates, different to sludge or thrombus, adhering to vein valves. They seem to summarise and indicate long-term effects of stasis, leading to at least six consecutive stages of vein valve destruction from impaired sinus function to the final loss of cusps. It is my favourite study tool to examine long-term effects of compression garment and certain medication, like Flavonoids.

In your opinion, what are the biggest challenges faced by interventional vein specialists today?

Phlebology is very traditional, too traditional. The challenge for both surgical and interventional specialists is to overcome the barriers of prejudice. Our opinion on venous insufficiency is from an era where there were no tools to determine a morphological and functional status of single valves, and thus no specific therapy. Today, we can do that—years and decades prior to symptoms. It is our ethical duty to invent and establish reasonable solutions for effective early stage treatments that save not just patients’ health, but also lots of money. Within 10 years, it should be possible to provide data on the medical and financial benefit of early stage treatments. Maybe physicians will have to adjust their performance and learn how to make money differently while insurances will fight to reduce their expenses.

What advice would you give to young vascular surgeons starting out in their careers?

In general—to look for the best forward-looking and limit-breaking teachers, and the shortest ways to international knowledge exchange. In particular—to become an ambidextrous sonographer and watch as many vein valves and blood motion patterns as possible, as ultrasound is likely to be the basic tool for phlebology for at least another one or two decades.

Can you tell us about your most memorable case?

There are so many! The first 50mm great saphenous vein to be nicely closed with a laser. The fashion model performing a lingerie show three days after extended spider vein treatment. The first 18-year-old with successful hyaluronan correction of a congenital vein valve leakage. The first “incurable” varix recurrency solved in a single session with viscous biomatrix sclerofoam. And a negative one: The first deep venous thrombosis which occured after 11,500 endovenous cases done without anticoagulants.

What have been the proudest moments of your career so far?

My first public speech, my first poster prize, my first scientific award… these were precious steps but no matter of pride. I am not satisfied with anything I have done so far, so there is a good chance the proudest moment is still to come. In my imagination, it will be the day that national committees accept that venous insufficiency is not at all chronic, but well treatable and preventable if discovered in early stages.

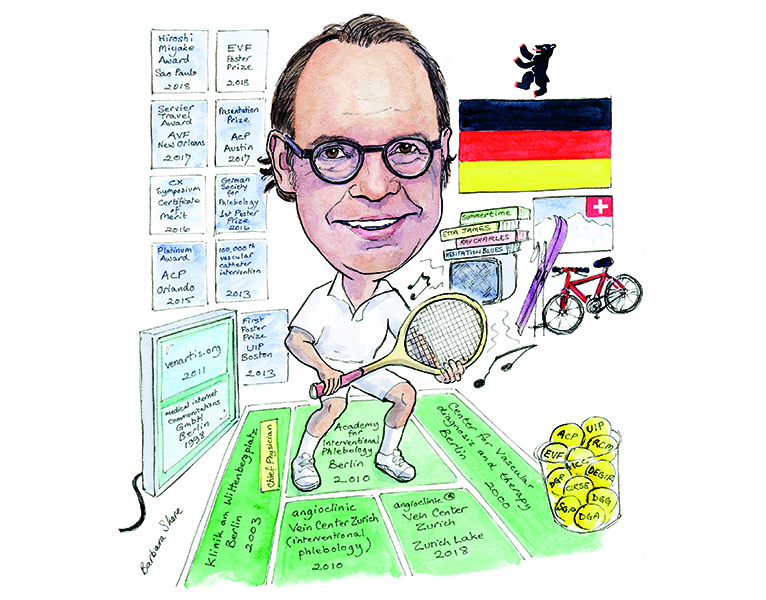

Outside of medicine, what do you like to spend your time doing?

I am an active tennis player, and I even take part in weekend tournaments in the 55+ category. Furthermore, my medical activities in Switzerland are a frequent excuse to add a weekend for mountainbiking or skiing, preferably with my wife and the kids. Concerning music, I love a slow blues to balance my hyperactivity and optimism.

Fact File

Career

2018 – Foundation of the new angioclinic Vein Center Zurich at Zurich Lake, Switzerland

2013 – 100,000th vascular catheter intervention

2011 – Foundation of venartis.org, non-profit organisation for innovations in Phlebology

2011 – Foundation of angioclinic Vein Center Zurich, Switzerland (interventional phlebology)

2011 – Foundation of “Akademie für Interventionelle Phlebologie“ (Academy for interventional phlebology), Berlin, Germany

2007 – Foundation of angioclinic Vein Center Munich, Germany (interventional phlebology)

2003 – Foundation of a private hospital for interventional vascular medicine, “Klinik am Wittenbergplatz Berlin GmbH“ in Berlin, Germany (chief physician)

2000 – Foundation of “Zentrum für Gefäßdiagnostik und Therapie” (Centre for vascular diagnosis and therapy, Berlin, Germany)

Awards and Prizes (selected)

2018 – Hiroshi Miyake Award Winner, IMAP International Meeting on Aesthetic Phlebology, Sao Paulo (Presentation on “Hyaluronan in Phlebology”)

2018 – EVF Poster Prize (Adjunctive hyaluronan instead of tumescence)

2017 – AVF, New Orleans: Servier Travel Award winner (Presentation on high-resolution ultrasound for vein valves

2017 – ACP, Austin: Presentation prize (Valve damage in children), poster prize (EHIT)

2016 – Charing Cross Symposium London: 2nd place, Innovation Forum, work on “Biomatrix Sclerofoam”; Certificate of Merit for presentation “Percutaneous valvuloplasty—a new way to vein restoration”

2016 – German Society for Phlebology, First Poster Prize (Biomatrix sclerofoam)

2015 – ACP, Orlando: Platinum Award – Percutaneous Valvuloplasty: Minimal-Invasive Restoration of Vein Valve Function Using Cross-Linked Hyaluronan

Memberships (selected)

American College of Phlebology (ACP)

Union International de Phlébologie (UIP)

European Venous Forum (EVF)

International Compression Club (ICC)

Royal Society of Medicine (RCM)

Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE)