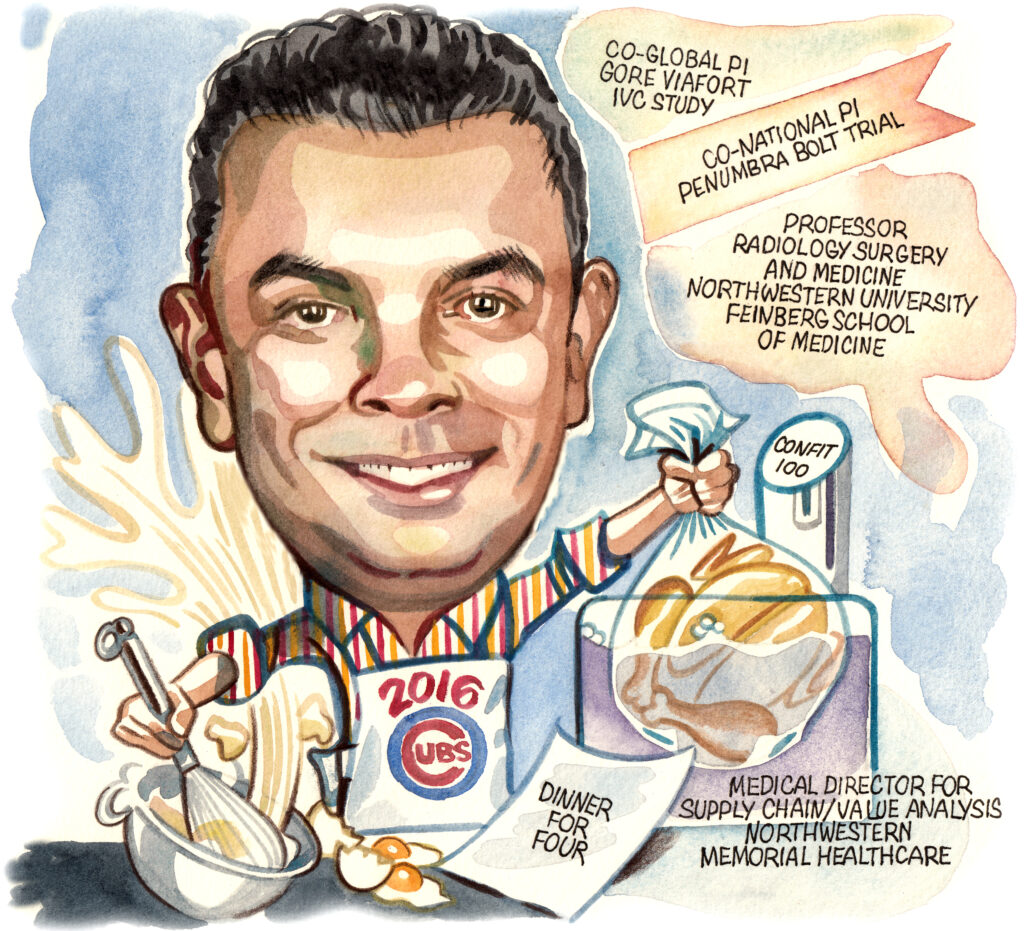

“One of the great and simultaneously worrisome things about venous disease is that we’re still in the first generation of our understanding of pathophysiology and therapies. It’s really exciting in the sense that there’s so much more to go in our lifetimes, and we can’t get complacent,” Kush Desai (Chicago, USA) tells Venous News while detailing his career and what’s next in venous care. In this interview, Desai, professor of radiology, surgery, and medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, goes into detail on why he pursued a career in medicine, the clinical trials he is currently working on, and what’s next in terms of venous disease care.

“One of the great and simultaneously worrisome things about venous disease is that we’re still in the first generation of our understanding of pathophysiology and therapies. It’s really exciting in the sense that there’s so much more to go in our lifetimes, and we can’t get complacent,” Kush Desai (Chicago, USA) tells Venous News while detailing his career and what’s next in venous care. In this interview, Desai, professor of radiology, surgery, and medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, goes into detail on why he pursued a career in medicine, the clinical trials he is currently working on, and what’s next in terms of venous disease care.

Why did you pursue a career in medicine and specialise in venous disease?

My path to entering a career in medicine was a bit circuitous. I was always aware of what a career and a life in medicine was like, because my mother is a retired physician. But it wasn’t one of those things where I knew that this is what I wanted to do from a young age; in fact, I really wanted to be a pilot and astronaut; I even went to Space Camp in Huntsville! Though my love of flight continues, it was through high school and my undergraduate years that I found I really enjoyed biological sciences and human physiology, and eventually found that a career in medicine was my calling.

My entry into the deep venous space, specifically, is a bit serendipitous. I’ve frequently said that where you end up and how you got there is a fascinating retrospective examination. If you had asked a 30-year-old version of myself if I believed that I’m going to become an expert in venous disease and venous intervention, I would not have believed it. Early in my career, I was given certain opportunities by my mentors, and then I just ran with it. One of the keys to career success, in my opinion, is identifying where the needs are, where you have the possibility of making significant impact, and the opportunity for sustained professional and personal growth. Then, find a professional community that you really cherish, with the best colleagues from around the world. This is how it happened for me, and amongst many things, ending up in this space with this community is one of the luckiest things to happen to me in my life.

Who have been your career mentors? What is the best advice they’ve given you?

I am the fortunate recipient of world-class mentorship through the different phases of my professional life. You look to your parents as your initial mentors to imbue a strong work ethic and personality traits that allow you to succeed. So, my parents were my mentors from the earliest of ages—and while that’s probably cliched, it’s true.

Shortly after I finished training, I was fortunate to be mentored by three people at Northwestern who offered me different things. Riad Salem really taught me how to be creative in problem-solving; he has always had an uncanny way of approaching complex issues. His career achievements are reflective of his innovative nature, and I’ve tried to follow that example.

Bob Lewandowski is one of my partners too, and he’s taught me the value of hard work, keeping your nose to the grindstone, and always seeking to improve yourself. From him, I have learned to never settle for less than the best version of yourself.

Bob Ryu also played a very key role in my early career. He’s the one that brought me into the venous space. He clearly recognised that a young academic physician needs something to ‘call their own’ to succeed, and he brought me into his and Lewandowski’s complex filter retrieval practice. He let me run with it, and he gave me an idea for a topic that would become, very early in my career, a bit of an academic ‘magnum opus’ in that inferior vena cava (IVC) filters can be removed, regardless of dwell time. Not only did he give me that chance, but he’s the one I would say that really taught me how to be a doctor, that the patient is at the centre of everything—your true north.

Moving into the venous space, there are a number of people who have taught me so much, including Steve Black, Gerry O’Sullivan, Erin Murphy, Suresh Vedantham, Akhi Sista, Ron Winokur, Gloria Salazar, Minhaj Khaja, Houman Jalaie, Nicos Labropoulos, Tony Gasparis, Steve Elias, Bill Marston, Mark Meissner, Kathy Gibson, and Raghu Kolluri. I’m sure I am forgetting someone! But that’s my community. They’re as close as colleagues as they are friends. I’m so lucky to be in the venous disease space, because I’m with best-in-class people, not just professionally, but personally.

On the industry side, I have made so many close friends, and I can’t possibly name them all. But I have embraced the fact that we, in vascular intervention, rely on industry as much as they rely on us. There’s a mutualism, and there’s a common goal to do better for our patients.

What would you say has been the most important development in the venous space over the course of your career thus far?

To me, the greatest advancement has been the broad recognition that venous disease impacts a wide cross-section of society, and that we need to do better. We need to devote specific people to solving these problems. Early on, there were very few people committed to this space. People like Suresh Vedantham, Tony Comerota, Peter Neglen, and Peter Gloviczki were in the minority.

Now, venous disease has firmly entrenched itself as a vital component of vascular disease, with a vibrant physician, scientist, and industry community behind it. That’s a great thing because not only are a lot of people suffering from venous disease, but the time horizon for the impact of venous disease on patients is so great, greater than I would argue for most other vascular diseases, and it deserves our attention and respect. Over the past several years, I think that’s finally happening.

To me, that’s the greatest development in venous disease, that we’re now paying attention. You see it reflected in the trials. There are now three randomised trials for acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and countless other trials in progress for pulmonary embolism (PE), acute DVT, post-thrombotic syndrome, and superficial venous disease. Innovation in this space is constant!

Can you outline some of the trials that you’re currently involved in and what trials you think are needed?

I have been involved in several important clinical trials and research efforts in venous disease, including C-TRACT, CLEAR DVT, and REAL-PE. I am also fortunate to serve in trial leadership as the co-global principal investigator (PI) of the Gore Viafort IVC study with Steve Black, where we are investigating the first purpose-built system for iliocaval obstruction. I am the co-national PI of the iliofemoral Viafort trial with Kathy Gibson. I am also co-leading Penumbra’s BOLT trial with Patrick Muck; this will examine the outcomes of intervention with the Indigo Lightning system for acute iliofemoral DVT.

Randomised controlled data are very important. That’s sort of the pinnacle of the pyramid of evidence, using large, multicentre datasets, and now that’s closely followed by real-world analysis. We’ve seen this with the REAL-PE study—a contemporary sampling of what’s going on right now in the real world in PE intervention. Real-world analyses give us the opportunity to make adjustments to current practice, to course correct if needed, or confirm the path we are on.

What we really need are long-term data from the venous space. These interventions have to be durable; patients should ideally have sustained improvement, on the order of decades in many cases. We know that’s not always the case with current approaches and technologies, and there’s a frequent need for reintervention. Specifically, within deep venous obstruction, I’d say the concept of maintaining, going back to the idea of stent maintenance—particularly in deep venous obstruction patients—is very important. We know that in post-thrombotics, which is a lot of what I do, patients have higher stent occlusion stenosis rates. So how do we bring the idea of lifelong surveillance and maintenance of the stents to these patients? What technologies do we need for debulking devices, crossing devices, and potentially devices or technologies built into the stent to slow down or even arrest the process of stenosis and occlusion? Our understanding of the role of inflammation in venous disease is growing, which I think is underappreciated, but it is growing, and people are starting to devote attention to it. To summarise, we need more durable outcomes, and the only way to promote progress in that direction is by following these patients longitudinally. Fortunately, I think the venous community understands that.

What do you think are the biggest challenges that the venous world is currently facing?

We’ve moved past the recognition part, and now one of the biggest challenges is speaking a common language in terms of research efforts and how we care for our patients. There’s been a lot of work that’s gone into getting people to speak a common language. I’m working with Steve Black on the Venous Academic Research Consortium and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to come up with common trial elements for deep venous obstruction. Ultimately, we want people to be collecting the same data, so that we can compare trials and therapies in rigorous ways.

Reimbursement and advocacy challenges are out there too. I know reimbursement remains a big issue worldwide, particularly in venous therapies, where the time and effort that goes into the care of these patients is not necessarily recognised. Part of this is on us. We must demonstrate that not only are these very difficult procedures, but also that they make material impacts on patients’ lives, improving quality of life and ability to contribute to society. Once we more clearly demonstrate the impact of these interventions, support will follow, because regulatory bodies will recognise how vital it is to maintain access for patients.

Could you outline one of your most memorable cases?

As I have mentioned, one of the great things about treating venous disease is the impact you have on patients can be long lasting, especially if you’re working on a 30-year-old for example.

One particular patient comes to mind: a patient with post-thrombotic iliofemoral venous occlusion. They had lost their ability to do the most basic tasks, though they were otherwise well. It wasn’t like a typical arterial patient, where there’s also heart failure, or they have diabetes; this patient strictly had this problem.

We tried to revascularise this patient, and we failed the first time. What I’ve found through my career is that, if you fail the first time you do something, that’s not necessarily the time to give up unless you identify that there’s something insurmountable. And so, while we initially failed, we learned a lot about the nature of the occlusion. In a second attempt, we failed again but added another layer of knowledge that informed the third, and final attempt, and that time, we were successful. This patient has had a 180-degree turn in their life, and the result has lasted. That’s why I do what I do.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a career in medicine?

Know that what you’re entering isn’t just a profession, it’s a calling. You have to embrace it, and it has to be for all the right reasons. Obviously, there’s a stable income and a good living, but there are easier ways to be financially secure than this. You need to love what you’re doing, and that means doing it for the right reasons—care of patients, and personal fulfilment in that pursuit. Make sure you avail yourself of all the available information and talk to lots of people and understand what you’re entering. If you do all those things, you’ll find that, like me, there’s nothing else you’d rather do.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

I’m the father of two wonderful boys, and they’re my everything. I have a lovely wife who is the glue that binds our family together. Everything runs because of her. She’s a physician herself.

Outside of work, I absolutely love to cook. Much to my family’s chagrin, the more complex the recipe in terms of ingredients and technique, the better. Sous Vide, confit, you name it. More obscure ingredients? Even better. I am also a beleaguered Chicago sports fan, though hope springs eternal. I’m still basking in the Cubs 2016 World Series victory!