Most existing surgical options for symptomatic deep venous insufficiency (DVI) with venous stasis ulcers either fail or provide limited success. Many surgeons consider operating on large veins such as the common femoral vein to be foolhardy—something new is required, believes John C Opie.

Any new innovative surgery that could involve complications such as bleeding, prosthetic vascular patch infection, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) with possible pulmonary embolus or delayed deep femoral vein occlusion, should not be performed on an industrial scale until carefully analysed to determine whether it is:

- Safe

- Reproducible regardless of expertise

- Produces minimal complications

- Effective in the short term

- Reverses insufficiency complications

- Effective in the long term.

The various causes of DVI have been understood for many years. They include both acquired (DVT and injury) and congenital (primary valve reflux), the latter not infrequently associated with May Thurner’s syndrome (either stented or unstented).

Typical symptomatic DVI venous stasis ulcer management is palliative. This includes long-duration high-force compression hose, professional scheduled wound care, local ulcer management debridement/dressing, antibiotics, skin grafting, hyperbaric oxygen, Unna boot, and leg elevation, among others. This palliative care has proven to be expensive and is generally associated with many failures and dissatisfied patients. Some are referred for amputation to be rid of the pain of non-healing ulcers. Palliative care for aggressive DVI could be viewed as a failure. DVI occurs in 0.5–3% of the adult population and will likely increase as populations age. Its management currently costs approximately US$1.6 billion annually in the USA alone. It is an old disease and distal leg and ankle ulcer development has been recorded as far back as the Eber’s Papyrus (1500BC).

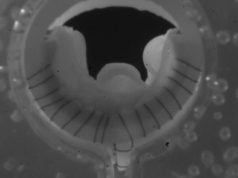

There have been multiple attempts to design and implant artificial valves in the common femoral vein but, to date, these have not been successful. Several investigators have proposed autogenous valves constructed from vein wall tissues (such as Maletti, Plagnol and Raju), but if the intima is separated from the adventitia, the intimal valve created is devascularised, it is likely to fail, calcify and be associated with DVT and or pulmonary embolism. Monocusp surgery was developed to try and reverse this expensive and disabling condition. The technique utilises full thickness anterior common femoral vein wall and a double suture suspended flap valve, thus keeping the monocusp viable and hormone capable, meaning it is likely to last a lifetime, provided the 60 prolene suspension sutures do not fail. Robert Kistner introduced the Kistner common femoral vein valve repair many years ago, and when primary valve reflux with usable valves is encountered, it is by far the preferred procedure. However, not infrequently in acquired deep venous insufficiency, there is no residual usable common femoral vein valve. For that reason, vein valve reconstruction surgery has languished and the disease has been considered largely incurable.

Monocusp implantation relies on four important concepts:

- The common femoral vein opening must be box-shaped to preserve the distal based flap.

- It must be full thickness vein wall (cleaned of connective tissue) to permit a vital flap which is hormone capable.

- The anticipated incision lines must be drawn on the vein before cross clamping.

- The vein defect must be closed with ultrathin ePTFE.

All common femoral vein incisions should be box-shaped to permit conversion to monocusp if a Kistner valve repair is impossible. If a single vertical vein incision is made, the monocusp option is surrendered and might lead to a sham procedure that will likely not help the patient.

Monocusp surgery began in 2002, and by 2005 29 monocusp surgeries had been completed in 26 patients. Two early technical failures occurred. One patient was discharged with an international normalised ratio of 1.2 and in the second patient the leading edge monocusp sutures were too long and the flap annealed to the ePTFE patch. Aggressive symptoms recurred quickly and both procedures were redone higher up with symptom resolution. There have been no late failures with the longest follow-up at 14 years and the shortest at 11 years in the initial series. If monocusp surgery fails and deep venous insufficiency reappears, the patient will quickly return to your office.

Recently, a patient flew in to me for treatment from another city. He had May Thurner’s syndrome and developed a full leg deep vein thrombosis managed with warfarin. His May Thurner’s syndrome was subsequently stented and he had persistent wide open common femoral vein reflux that was accelerated with a supine Valsalva manoeuvre on deep venous ultrasound. He sustained typical very painful medial and lateral multiple venous stasis ulcers, and after 11 years of DVI treatment failures was advised that his condition was incurable and no further treatment was offered. He met a Texas Army doctor who had been at a meeting at which monocusp surgery was presented. She advised him to contact our facilities and, after full work-up, monocusp surgery was completed with postoperative Eliquis anticoagulation. Patients lying supine who have DVI at rest that resolves with a Valsalva manoeuvre will typically have primary valve reflux, and a Kistner procedure is an excellent plan. Patients whose DVI accelerates during supine Valsalva will likely have un-reconstructable common femoral vein valves and monocusp surgery should be planned.

John C Opie is at Optima Vein Care, Phoenix, USA

References

- JC Opie, T Izdebski, DN Payne, SR Opie. Phlebology 2008;23:158–171.

- GB Agus. Angéiologie, 2009:61,2;52–61.

- JC Opie, P Sos et al. Vascular Disease Management 2010;1–6,7,10 (available online).