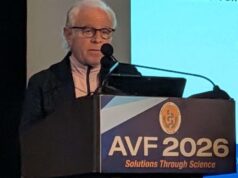

Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters have been a highly controversial topic in the field of venous medicine due to the high rates of complications associated with their use, which eventually prompted a 2010 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory and declining use. This year, an article by the editor of JAMA Internal Medicine—Rita F Redberg (University of California, San Francisco, USA)—suggested, “There should be a moratorium on [IVC filter] use unless or until there are data showing efficacy greater than risk.” At the 2017 THE VEINS at VIVA meeting (10–11 September, Las Vegas, USA) Venous News spoke to John Kaufman (Dotter Interventional Institute, Portland, USA) to hear his opinion on the moratorium call, and how IVC filter use can be optimised for the safest and the best outcomes.

Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters have been a highly controversial topic in the field of venous medicine due to the high rates of complications associated with their use, which eventually prompted a 2010 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory and declining use. This year, an article by the editor of JAMA Internal Medicine—Rita F Redberg (University of California, San Francisco, USA)—suggested, “There should be a moratorium on [IVC filter] use unless or until there are data showing efficacy greater than risk.” At the 2017 THE VEINS at VIVA meeting (10–11 September, Las Vegas, USA) Venous News spoke to John Kaufman (Dotter Interventional Institute, Portland, USA) to hear his opinion on the moratorium call, and how IVC filter use can be optimised for the safest and the best outcomes.

Discussing the JAMA article, Kaufman argued that the call for a halt on IVC filter use “is a very dangerous point of view,” suggesting instead that “very careful and thoughtful use of these devices is the way forward.”

“There is no doubt that patients with DVT get pulmonary embolism, and there is no doubt that patients with pulmonary embolism have morbid outcomes. If these patients cannot be treated with anticoagulation, the filter remains the only option we have right now to prevent either recurrence or primary pulmonary embolism in patients with established venous thromboembolic disease,” Kaufman said.

“To suggest that we should stop using IVC filters in all patients because we have never proven the value of filters to prevent death and morbidity from pulmonary embolism in patients with VTE who cannot be anticoagulated is, I think, not in the best interests of our patients. Careful, judicious use with careful follow-up is in their best interests.”

When to place

As for when is appropriate to use IVC filters, Kaufman said, “The primary indications are patients who have established thromboembolic disease—such as DVT, proximal DVT, or pulmonary embolism— who cannot be treated with primary therapy which is anticoagulation, and who are considered at high risk for pulmonary embolism. The function of these devices is to prevent pulmonary embolism, so this is why they should be used.”

Kaufman noted that one of the most significant areas of controversy is when patients do not have established venous thromboembolic disease, but are considered to be at risk of developing it, when they cannot be anticoagulated or cannot have DVT detected, such as trauma patients, some preoperative patients, and so on. “That remains a very controversial area, and IVC placement should be done on a very selective case-by-case basis,” he cautioned. “All placements should be done in conjunction with consultation of all of the physicians taking care of the patient. In particular, when placing a device in someone who does not yet have venous thromboembolic disease, this should be done in a very thoughtful and deliberative manner.”

Planning is paramount for filter removal

Just as important as deciding that a patient is suitable for an IVC filter is planning for its removal, if necessary. While permanent devices are available, “all of the recent devices that have been recently approved are meant to be used only for the period of highest risk, although most are approved for permanent use.” “Devices should be removed as soon as possible once the patient is no longer at risk of pulmonary embolism, which usually means after establishing stable anticoagulation, normally for at least two weeks. The single most important factor in getting a filter out is planning on removing it. When the filter goes in, it is the responsibility of the individual placing the filter to determine the plan for follow-up with the goal of filter removal if appropriate in that patient. Not all filters should be removed and not all need to be removed, but establishing that plan up-front is the single most important factor in achieving successful removal.”

What the future holds

One of the biggest factors to consider when thinking about the future path for IVC filters “is the litigious environment surrounding these devices right now,” Kaufman said, “which is a disinhibition potentially even for the current manufacturers to stay in the filter market, and means that there is very limited interest in new devices at this time.”

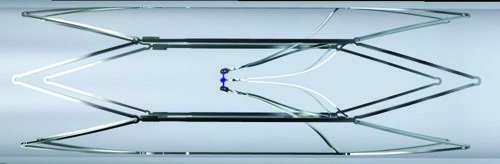

Most of the devices currently in development are trying to address the problem of removal, and the fact that not enough filters are being taken out. One such option is the Sentry bioconvertible filter (Novate), which consists of a stable frame with filter arms held together by a bioabsorbable filament. This provides protection against pulmonary embolism during the transient risk period (approximately 60 days), before bioconverting via hydrolysis and releasing the arms which then retract to the IVC wall, leaving a patent lumen.

There is also a completely absorbable filter in the works at Adient Medical, for which the goal is to avoid a residual filter left in the IVC. Another is the Angel filter (Bio2 Medical) which is a tethered, catheter- based device, which has to be removed.

“The issues with filter retention and difficulty of removal are driving most of the development in this area,” Kaufman said. “This trend does not address those people that need to have filters permanently, but we already have devices that can be used in this manner. Devices with a permanent indication should be used in patients who have no clear endpoint in sight for their need for pulmonary embolism protection.”

“It is a very challenging area because of the clinical concerns over the devices, the litigious environment and the contraction in the market. This all decreases incentive for manufacturers to develop new devices, and possibly to remain in the market. Yet, these remain essential devices, and patients will die if we do not have IVC filters. We need the devices, we need the research and we need people to continue to innovate. One of our responsibilities as physicians is to help support this new knowledge and development as we go forwards through studies such as the PRESERVE trial in the USA.”

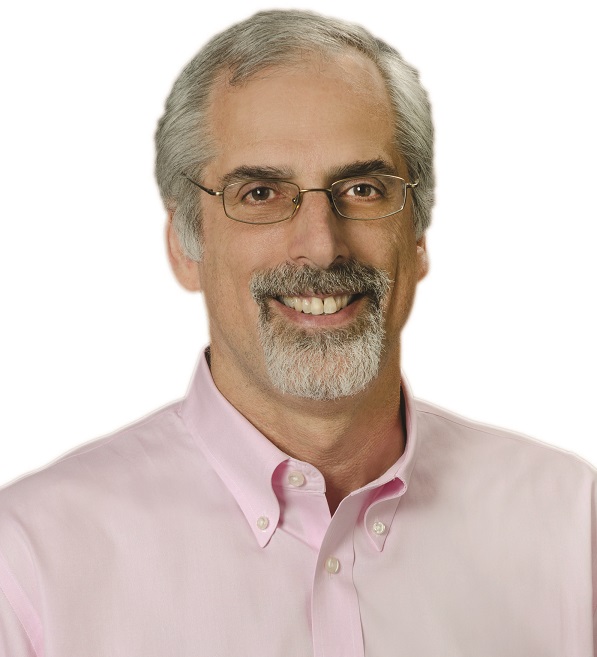

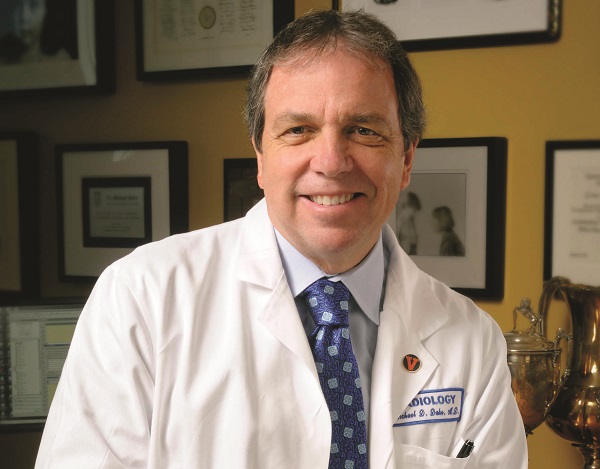

SENTRY trial offers a “a new perspective” on IVC filters

At the VIVA meeting, 12-month results from the SENTRY trial evaluating the Sentry bioconvertible IVC filter have shown a 0% rate of symptomatic pulmonary embolism, no instances of device failure and a 96% rate of bioconversion. Presenting that data, principal investigator Michael Dake (Stanford, USA) said that the data represent “an important paradigm shift in the prevention of pulmonary embolism”.

The issue of pulmonary embolism, unlike IVC filter use, “is not controversial,” Dake said, with an incidence of 400,000–600,000 each year in the USA alone, accounting for 50,000–200,000 fatalities. One in every 10 hospital deaths is pulmonary embolism-related, and each event costs approximately US$52,000 to treat. “Used correctly, IVC filters save lives and reduce injury and cost related to pulmonary embolism, while survival benefit has been shown in appropriate populations,” Dake argued. However, he continued, “Existing retrievable technology has not met the needs of patients and healthcare systems.”

The Sentry IVC filter—which received FDA 510(k) clearance in February 2017—is designed to provide protection against pulmonary embolism during the transient risk period, before bioconverting to release the arms which then retract to the IVC wall, leaving a patent lumen. This reduces the risk of IVC occlusion and removes the dangers and costs associated with filter retrieval. The FDA has published two warning letters recommending the retrieval of IVC filters after the transient risk period for pulmonary embolism subsides, which is typically beyond 30 days.

The SENTRY trial enrolled 129 patients requiring pulmonary embolism protection across 23 sites. Of those enrolled, 67.5% had current pulmonary embolism and/or DVT at the time of enrolment. All patients had contraindication to anticoagulation for all or some of the protection period. The primary factor for filter placement was surgery (n=77, 59.7%), followed by medical condition (n=28, 21.7%) and trauma (n=8, 6.2%).

The trial is “one of the most imaging-intensive studies conducted to date” analysing IVC filters, Dake noted, using ultrasound and venogram for the index procedure, ultrasound and computed tomography venography at one month, X-ray at two months, computed tomography at six months, X-ray at 12 months and computed tomography venogram at 24 months.

Dake reported 100% technical success and 100% freedom from symptomatic pulmonary embolism out to 60 days. There were two (1.8%) symptomatic caval thromboses which were treated and did not reoccur. There was no device tilting, migration, embolisation, fracture or perforation. At 12 months, no new symptomatic pulmonary embolisms were reported and there were no device-related complications. No secondary filters were placed to extend the pulmonary embolism protection period beyond 60 days. The bioconversion rate of the filter filament was 96%, which “compares favourably” with published retrieval rates, Dake said. In the 18 patients who had a clot identified in the filter via one-month computed tomography venography, there were no symptomatic pulmonary embolisms. No IVC stenoses were reported at 12 months.

“This study offers us a new design and a new perspective on IVC filtration,” Dake concluded. Two-year follow-up is currently in progress.

As to the idea of a moratorium on IVC filters, Dake told Venous News, “Venous thromboembolic disease and, in particular, pulmonary embolism is a significant healthcare problem that accounts for almost 200,000 deaths per year in the USA alone. Used correctly in the appropriate patient populations, IVC filters save lives and reduce the morbidity and cost related to pulmonary embolism.”

“As is often the case with medical devices, the ongoing challenge is to better understand the type of patients who will benefit most from the application of an interventional technology. Disadvantaging patients and risking lives by withdrawing access to all IVC filters because precise definition of risk to efficacy data is currently unavailable for a range of patient subgroups at risk of pulmonary embolism is an overly simplistic reaction to a complex issue that is best served by a more reasoned approach to determine the legitimate role of IVC filters in the management vulnerable venous thromboembolic patients.”