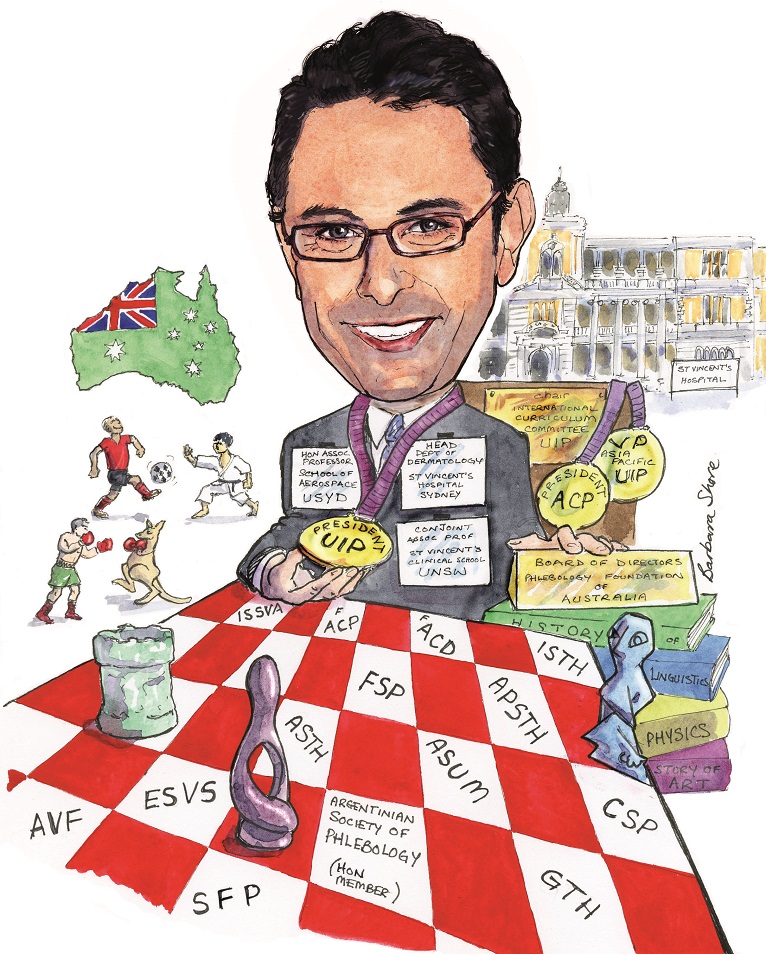

Kurosh Parsi, incoming president of the International Union of Phlebology, or Union Internationale de Phlebologie (UIP), is an Australian dermatologist, phlebologist and vascular anomalies specialist who pioneered catheter-guided and tumescent-assisted sclerotherapy.

With his broad range of expertise and varied research, Parsi sees phlebology as an “inter-connected multiverse” of disciplines, in need of further recognition as a specialty.

What led you to study medicine and specialise in phlebology, dermatology and vascular anomalies?

Medicine was my second or third choice. I was more interested in physics and aeronautical engineering. I was also interested in medical research, so I decided to study medicine. After I finished Medicine—and by pure coincidence—I attended a meeting where this enigmatic and incredible person, Dr Louis Grondin, president of the Canadian Society of Phlebology, was giving a lecture on pelvic congestion syndrome. For me that was it, and at that moment in 1994 I knew phlebology was my future field. I started working in a phlebology practice, visited Louis in Canada and joined the Sclerotherapy Society of Australia where I met another inspirational person, Dr Paul Thibault, who taught me and many others how to perform ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy.

I then completed a Masters degree investigating the risk factors for Traveller’s Thrombosis. My supervisors were Professor Reg Lord and Dr Michael McGrath, two true vascular legends in Australia and Professor David Ma, an inspirational haematologist.

Having travelled to the USA a number of times, I met Bob Weiss, Mitch Goldman and Neil Sadick and observed how dermatology and phlebology can overlap. I decided to specialise in dermatology. After four years of fellowship training, I started working as a dermatologist at St. Vincent’s hospital in 2004 while practicing phlebology from my private rooms. I have been the head of department for the past 10 years.

Over the years, I developed an interest in venous thrombosis and wanted to study the interaction of sclerosants with the coagulation system. This led me to a PhD with the haematology team at the Haematology Research lab at St. Vincent’s hospital. I completed my PhD under the close supervision of David Ma and Dr Joanne Joseph. I met David Connor, another PhD student at the Haematology Research lab and we have been friends and research collaborators since then. Following the completion of my PhD, together with David we established the Dermatology, Phlebology and Fluid Mechanics research laboratory at St. Vincent’s Centre for Applied Medical Research.

As a dermatologist and phlebologist, I became interested in vascular anomalies, joined the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) and met Prof BB Lee. He has been one of my true mentors over the years. I subsequently digressed to interventional radiology and worked at Sydney Children’s Hospital for around ten years treating vascular malformations. Currently 40%–50% of my private practice is paediatric and adult vascular anomalies.

So, how do I visualise phlebology? I think of phlebology as an inter-connected multiverse, where multiple universes of vascular medicine and surgery, paediatric and adult vascular anomalies, haematology, dermatology, interventional radiology and lymphology come together. It is truly a rich and colourful specialty with a wide scope.

Who have been your professional mentors, and what lessons did you learn from them?

Louis Grondin was my first and most important inspiration. Louis has this amazing capability of seeing what most ordinary people cannot see. Phlebology becomes a multi-dimensional universe when you look through Louis eyes. He is an extraordinary person with an extraordinary gift. He is also a gift to phlebology and we should feel lucky to benefit from his genius.

Over the years, I have met, been inspired and encouraged by other legends of phlebology such as Paul Thibault (Australia), JJ Guex (France), Michel Schadeck (France), Ken Myers (Australia), Andre van Rij (New Zealand), Mark Malouf (Australia), Hugo Partsch (Austria), Alun Davies (UK), Eberhard Rabe (Germany), AA Ramelet (Switzerland), Attilio Cavezzi (Italy), Lorenzo Tessari (Italy), Mark Meissner (USA) and Steve Zimmet (USA), amongst many more who have inspired me personally as a phlebologist. Amongst non-phlebologists, Prof David Ma (haematologist, Sydney, Australia) and Prof Steven Kossard (dermatologist and dermatopathologist, Sydney, Australia) have been great sources of inspiration and encouragement for me in the past three decades.

The most important thing I have learned from these amazing people is to stay humble and to know what I do not know; to know that we still have a long way to go and that there is still so much to learn and discover.

What are the most significant ways you have seen the venous field develop over the course of your career?

The French school of phlebology and the development of ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy (UGS) pioneered by Michel Schadeck and Frederic Vin changed the field of phlebology forever. We should all be grateful for their enormous contribution.

UGS became a much more effective procedure with the introduction of foam sclerosants pioneered by Juan Cabrera (Spain) and Lorenzo Tessari (Italy). Again, foam has made a huge difference in our treatment outcomes thanks to the genius of Juan and Lorenzo.

I pioneered catheter-guided sclerotherapy and published the technique in 1997. The catheter-guided concept evolved into endovenous laser and radiofrequency ablation. Endovenous catheter-guided procedures are the now norm and the first-choice treatment in the hierarchy of treatment options for venous disease. Finally, tumescent-assisted sclerotherapy (TAS) has been pioneered by myself, Paul Thibault and Attilio Cavezzi, as well as Greg Spitz. This will take sclerotherapy to a different level.

How do anticipate the field might change in the next decade, and what developments would you most like to see realised?

We desperately need better and more practical treatment options for deep venous disease and in particular deep venous reflux. Post-thrombotic syndrome desperately needs a new instrument to replace the Villalta score. Lymphoedema needs its own ultrasound-guided intervention.

With superficial venous disease, we need to define the end point of venous interventions. A lot of treatments are performed in a haphazard fashion. Veins get ablated in bits and pieces resulting in sub-optimal outcomes for patients. I am advocating an A-to-Z approach, where practitioners treat the vein and the associated venous system in its entire length, not skipping segments or tributaries. I would like us to be a lot more scientific in our approach to venous disease and less random.

In the last year, which new paper or presentation has caught your attention?

Mark Meissner’s pioneering work with pelvic venous disease; Steve Black’s inspirational passion for venous stenting and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS); Nicos Labropoulos—I can listen to him talk about anything for ever—and Tony Comerota with his outstanding research on deep venous disease.

What has been the proudest moment of your career to date?

Receiving the Gold Medal of the Australasian College of Phlebology.

What are your current areas of research and work?

The dermal microcirculation and reticulate eruptions such livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa. Do reticulate eruptions correlate with structural changes in the underlying reticular veins and the dermal microcirculation?

As president of UIP, how do you hope to shape the society and further its progress during your presidency?

My election to president was uncontested and unanimous having received 100% of the votes (90 of the 90 votes). My colleagues’ tremendous confidence in me is a great compliment, but at the same time has given me an unquestionable responsibility to make sure I act on behalf of all of them, representing all member societies and all countries equally. This is clearly my top mandate, to represent the UIP in its entirety, to protect the interests of the UIP and all its member societies. Their vote of confidence has also given me a strong mandate to bring about reforms to the UIP. My main aim in the next four years will be to resolve the chronic pathological problems that have entangled the UIP machinery and blunted its growth for decades. My mandate is to make the UIP processes crystal clear, structured, fair, simple, efficient, non-factional, non-political and highly organised. I need the full support of the phlebology community in the next four years to achieve tangible results. We have already started constitutional reforms and significant reforms in the congress management. I also would like to expand the UIP. By the end of the UIP Chapter meeting in Krakow, we will have more than 70 member societies in the UIP. My aim is to reach the magic number of 100 member societies by the 2023 World Congress.

Other than organisational reform, it is my personal passion to encourage true scientific activities and try to re-shape the UIP from a politically-focussed organisation to one renowned for science and education. Our first step was to introduce the UIP online education programme in January 2019. The educational modules have been a solid aspect of the Australasian College of Phlebology (ACP) formal phlebology Training Program in Australia and New Zealand and have been very popular with the College trainees. The modules will support the UIP phlebology curriculum and ensure a similar level of exposure to educational materials irrespective of where people live and will introduce minimum training standards across all continents. Each module is taught over a two-week period by an instructor, but the contents are available permanently and can be accessed at any time. Each module is comprised of course materials that may include power points, videos and articles. The user simply needs to login, read any prescribed articles or information as uploaded by the instructor and then complete an online assessment to pass that module. Subscription to the modules is for one-year access to all modules within the system. Trainees can determine at which pace they would like to continue through the program. Should they need more time to work through the modules they will need to subscribe for another year of access to the online modular system. There are significant discounts for tier 2 and Tier 3 members of the UIP.

Why is it important that a society like UIP exist?

UIP is the peak body representing phlebology on a global level. With more than 70 member societies from across five continents, the UIP provides an international forum for the interaction of venous specialists. UIP Congresses provide a great opportunity for talented phlebologists to meet, greet, be inspired, be encouraged and energised. The UIP Congresses remind us that we belong to a large global phlebology family. In addition, the UIP can provide support to its member societies, facilitate international guidelines and research initiatives and help with education of both doctors and patients. Ultimately, the UIP is there to help raise the standards of care for patients with venous disease.

What advice would you give someone at the start of their career in phlebology?

Think outside the box. Do not believe everything you read in the textbooks, especially the older ones. When people tell you “I have been doing this for 20 years and have never had any problems”, remember they may have been doing it badly for 20 years and the patients were the ones who had the problems! Question everything and think independently.

In your opinion, what are the biggest challenges currently facing specialists in this field?

Lack of recognition of phlebology as a medical specialty by health authorities has hampered our efforts in increasing the standards of care for patients with venous disease on a large scale. While standards are very high in some countries, they are very poor in many countries. My ultimate aim is to gain recognition of phlebology as a multi-disciplinary specialty around the globe. Thus will help with increasing the standards of patient care, increase public education on important topics such as chronic venous ulcers and increase the standards of training.

Could you tell us about one of your most memorable cases?

Three-year old child with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome with a leg looking like a 90-year old booked for below-knee amputation. I saved that leg, and not by a miracle, but by simply applying good phlebology skills to a complex vascular problem.

How do you like to spend your time outside of work?

With my family and close friends. With my wife Yana and young daughter Parmiss doing Maths and Physics or rehearsing her presentations for school. Doing a lot of sports every day, planning our next party or trip and working on my next research paper! Finally, add learning Spanish to the list. Never a dull moment!

We will have s great future with UIP.

Let’s go mr president Parsi!