Emerging evidence suggests that the lymphatics play an important role in the early pathogenesis and progression of peripheral arterial and venous diseases, suggest John Rasmussen and Eva Sevick-Muraca, writing for Venous News.

Functioning peri-adventitial lymphatics are essential for reverse cholesterol transport by macrophages to maintain or “cleanse” the arterial walls of cholesterol.1 When there is lymphatic insufficiency, localised oedema in the intima and tunica media, smooth muscle cell degeneration, and macrophage accumulation may occur and precede atherosclerotic plaque formation. Likewise in venous disease, reduced numbers of lymphatic vessels and increased lipid content has been found in the adventitia of incompetent great saphenous veins of patients presenting with venous varicosities.2 Tissue oedema is also a well-known clinical symptom of peripheral vascular disease that results from (i) excess capillary filtration from inflamed or occluded blood vessels, (ii) incompetent fluid uptake and transport by an abnormal lymphatic vasculature, or (iii) a combination of both. Today, surgical treatments focus upon revascularising the blood vasculature, but if lymphatic insufficiency is associated with pathogenesis and progression of peripheral vascular disease, then durable outcomes may be limited without considering the lymphatic component. Furthermore, if lymphatic insufficiencies are found to be an early contributing factor for the development of peripheral vascular disease, then new therapeutic strategies to modulate the immunelymphatic system could be developed as an adjuvant to improve surgical outcomes.

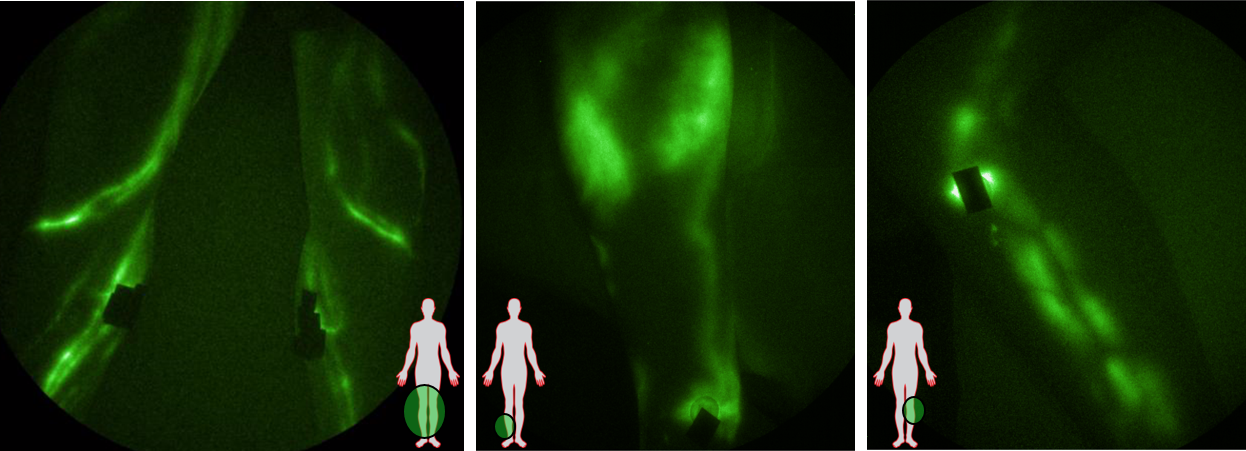

Using trace intradermal injections of indocyanine green (ICG) and custom, optical instrumentation that adapted night vision technology for increased imaging sensitivity, our team has previously shown that the lymphatic vasculature in the legs are normally straight and comprised of mini-segments termed “lymphangions” that actively pump lymph (often against gravity in the lower extremities) and provide the driving force for the unidirectional flow through the “open” lymphatic system. However, in patients with chronic venous ulcers, we found that lymphangion pumping is impaired, presumably resulting in extravascular pooling of ICG-laden lymph at ulcer sites and at contralateral non-ulcerated ankles.3 More recently, we have begun imaging the lymphatics in the lower extremities of patients diagnosed with early venous or arterial disease. While enrolment continues, our preliminary results show dilated lymphatic vessels that exhibit varicosities and impaired lymphangion pumping in both venous and arterial disease. In addition, retrograde lymph drainage into the dermal lymphatics, which we and others term “dermal backflow,” occurs presumably due to the weakened lymphatic pump. These functional and anatomical abnormalities are not seen in all patients, but seem to occur even in the absence of overt lymphoedema or phlebolymphoedema. Nonetheless, lymphatic insufficiency is evidence of an impaired immune system that may be the cause of, or contributing to peripheral vascular disease.

Comparatively little is known about the lymphangion pump and the factors that govern its activity.4 Animal studies show that pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF, IL-1β and IL-6 result in arrest of the “lymph pump” and that administration of inducible nitric oxide synthase or an anti-TNF agent into the lymphatics can reverse this loss of lymphatic function.5,6 Whether these and other pharmaceutical strategies can be developed to stimulate lymphatic function in patients with peripheral vascular disease remains an active area of investigation. In the meantime, physiotherapies that include manual lymphatic drainage and pneumatic compression devices may alleviate the lymphatic insufficiencies that may otherwise contribute to the early progression of peripheral vascular diseases.

John C Rasmussen is Principal Investigator and Assistant Professor of Molecular Medicine, and Eva M Sevick-Muraca is Professor and Kinder Distinguished Chair of Cardiovascular Research at the University of Texas Health Science Center-Houston, Houston, USA

References

- Randolph GJ, and Miller NE. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(3):929–35.

- Tanaka H, Zaima N, Sasaki T, et al. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(5):1440–8.

- Rasmussen JC, Aldrich MB, Tan IC, et al. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2016;4(1):9–17.

- Kunert C, Baish JW, Liao S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(35):10938–43.

- Aldrich MB, and Sevick-Muraca EM. Cytokine. 2013;64(1):362–9.

- Aldrich MB, Velasquez FC, Kwon S, et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):116.