Jan Heyligers and Patrick Vriens, Tilburg, The Netherlands, write about a technique using the great saphenous vein for the reconstruction of an infected aorta. The technique, defined as a “see one, do one” procedure, was presented at the Charing Cross Symposium in April.

Infection of an aortic aneurysm or (endo)vascular graft is a rare but severe condition posing a serious clinical challenge. Percutaneous drainage and an antibiotic regimen may offer a temporary solution. However, radical surgical debridement and in situ autologous reconstruction are the cornerstones of long-term, infection-free success. The Tilburg group has successfully introduced the spiral vein technique using the great saphenous vein to construct a tailor-made autologous neo-aorta in infected cases, with good and reproducible results.

Background and implementation of the technique

Infection of the aorta is a severe condition and a challenge to vascular specialists worldwide. The aorta has either been initially infected, or—in most cases—infected after surgical repair. Infection is seen in about 1–3% of cases after aortic aneurysmal repair, and morbidity and mortality are high. Patients may suffer from severe sepsis. CTA, PET scan analysis, guided puncture and culturing are obligatory for the definite diagnosis. Often an aortoenteric fistula is the underlying cause of the infected aneurysm (graft). Cultures can show various bacterial pathogens, both Gram negative and positive. Primary infection with Coxiella burnetii bacteria in patients with chronic Q fever is notorious in the southern part of The Netherlands.

Leaving the infected aorta untreated can lead to death in up to 80% of cases. We first published our spiral vein technique in 2006 for a ruptured primary infected aneurysm. The patient did well and was on antibiotics for only three months after surgery. She survived more than eight years with no signs of reinfection. This initial success—in a ruptured case—prompted us to further develop this innovative technique. In 2010, we published the results of five patients treated with spiral vein reconstruction of the infected aorta. The technical success of the procedure was 100% and 30-day survival 80%. These data were compared to a cohort of patients treated in our institution with the Glagett-Nevelsteen procedure, using the femoral vein. Our results with spiral vein were at least as good, but with less morbidity, as there is hardly any morbidity in harvesting the great saphenous vein. Furthermore, the spiral vein technique allows for creating a conduit of any desired length and diameter. Other techniques, like replacement with impregnated grafts, xeno-grafts, extra-anatomical bypass or percutaneous drainage with life-time antibiotic regimen, do not totally eradicate infection and therefore are inferior to venous autologous replacement.

Technique

The great saphenous vein is harvested using longitudinal incisions in the leg. The vein is isolated and side branches are ligated using vicryl 4.0. The vein is then cut open longitudinally to create a ribbon that is wrapped around a tube of any desired size to create a neo-aorta. To calculate the length of vein that is needed, CTA reconstruction of the aorta is performed to measure the required length of the conduit. By using the formula 2πr (r=half of the diameter of the vein), the needed length of the vein can be calculated.

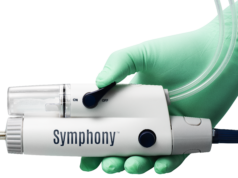

The vein is then sutured around the tube using a non-absorbable monofilament 6.0 wire (eg. Vascufil or prolene) (Figure 1).

In the meantime, a second team performs the abdominal phase. A midline laparotomy is performed and the infected aorta is exposed. After radical surgical removal of the infection and the infected graft, the constructed spiral vein is sutured in with a monofilament 4.0 wire using an inlay technique (Figure 2). Before closure the omentum is divided and brought to the neo-aorta in a retro-colonic fashion by an opening in the mesenterium (Figure 3). The spiral vein reconstruction is covered with omentum as an adjunct on the infected area. The abdomen is then closed in a conventional way. Antibiotics are continued up to three months after surgical repair, on the basis of pre- and perioperative culture results.

Results

The technique has been adopted by several other Dutch vascular centres. Up to now, 28 patients have been treated using this technique. The results were presented during the Charing Cross Symposium (28 April–1 May, London, UK) in the CX Innovation Showcase sessions. They were quite similar to the first five patients that were analysed and published in 2010. Of 28 patients (almost all male), 16 were treated for infection after aortic repair. We report technical feasibility of 100% in this series and a 30-day survival of almost 80%. The one-year survival is 69% and reinfection has not been seen with a median follow-up of nine months. No morbidity of the retrieval of the greater saphenous vein has been reported. Interestingly, follow-up CT scans have not shown dilatation of the spiral vein neo-aorta in any of the long-term surviving patients.

A technique to adopt

Infection of the aorta remains a severe and challenging clinical condition. We continue to develop and improve innovative techniques to create the best outcomes for our patients. Fortunately, aortic infection is a rare condition that vascular specialists (hopefully) hardly see in their daily practice. As the exposure is low for individual surgeons, this easy-to-adopt technique seems a solution for vascular surgeons all over the world. This is a “see one, do one” procedure. Every vascular surgeon is welcome to visit our website www.spiralvein.org to see the spiral vein technique and bring it to their patients in need. Feel free to contact us and share your results.

Jan Heyligers and Patrick Vriens are consultant vascular surgeons, Department of Vascular Surgery, Elisabeth TweeSteden Hospital, Tilburg, The Netherlands